There is a specific kind of magic that happens in the San Diego early morning mist, right before the sun burns through the marine layer. I’m standing in row four of my orchard, boots sinking slightly into the mulch, looking at what I consider the heavy lifter of the fruit world: the Brown Turkey Fig.

Meeting the Brown Turkey: More Than Just a Fig

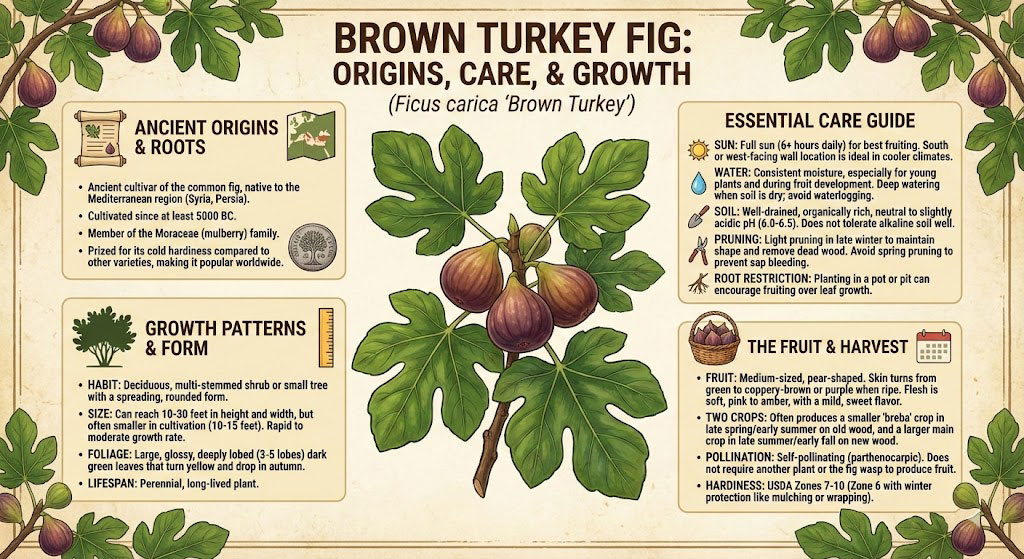

To the botanists, it is known as Ficus carica, but out here in the field, we have a dozen names for it. You might hear old-timers call it the “San Piero,” “Aubique Noire,” or simply the “California Turkey.” Regardless of the label, this deciduous tree is the backbone of many Southern California orchards. It is distinctive because of its brownish-purple skin and pinkish-amber flesh, but what truly sets it apart is its resilience. Unlike the delicate Kadota, the Brown Turkey handles our occasional winter chills and our scorching August heatwaves with equal indifference.

The Brown Turkey is often called the “everbearing” fig because, under the right conditions, it produces two distinct crops: the early “breba” crop on last year’s wood and the main crop on new growth.

My journey with this variety started fifteen years ago with a single cutting from a neighbor in Chula Vista. I stuck it in a five-gallon bucket, mostly out of curiosity. Today, that single genetic line has populated half an acre of my property. Here at Exotic Fruits and Vegetables, we’ve found that the Brown Turkey serves as the perfect gateway fruit for novice growers because it forgives mistakes that would kill a citrus tree instantly.

Soil, Sun, and Sweat: Creating the Perfect Home

You cannot cheat the soil. I learned this the hard way when I tried to plant a row directly into the native San Diego adobe clay without amending it. The trees sat there, stunted and yellow, for two years. Figs have a fibrous, spreading root system that hates “wet feet.” If the water sits, the roots rot.

For optimal growth, you need to mimic the Mediterranean drainage these trees originated in. I now mound my trees on berms raised 12 to 18 inches above grade. My soil mix is 40% native soil, 30% coarse sand, and 30% composted steer manure. This blend creates a pH between 6.0 and 6.5, which is the sweet spot for nutrient uptake. If your soil is too acidic (below 5.5), the tree locks out magnesium, and you will see the leaves turning bizarre colors.

Ever wonder why your neighbor’s neglected fig tree grows better than your pampered one? It’s likely because they aren’t drowning it with kindness—or water.

Sunlight is the engine that drives sugar production. I ensure every tree gets a minimum of 8 hours of direct, unfiltered sunlight. If you plant this tree in the shade of a house or a larger oak, you will get plenty of beautiful, large green leaves, but the fruit will be insipid and dry. The leaves act like solar panels; if they don’t get fully charged, the fruit doesn’t get sweet.

The Water Paradox

Watering is where most people fail. I used to water a little bit every day, thinking I was helping. That was a disaster. Shallow watering encourages roots to stay near the surface, where they bake in the July heat. Now, I apply 15 gallons of water per mature tree once every 7 to 10 days during the summer. I use a drip line with emitters spaced 12 inches apart in a circle at the dripline of the canopy.

Consistency in watering is actually more critical than the total volume; irregular watering cycles are the number one cause of fruit splitting right before harvest.

The Art of the Prune: Controlling the Chaos

Left to its own devices, a Brown Turkey Fig will become a 25-foot sprawling mess of gray wood. I treat pruning like air traffic control—I need to clear the runways. I keep my trees pruned to a manageable 7-8 feet, using an “open vase” structure. This means I remove the central leader trunk and encourage 3 to 4 main scaffold branches to grow outward.

Be careful when pruning! Fig trees bleed a milky white latex sap that is phototoxic. If you get it on your skin and then go into the sun, it causes blistering burns similar to poison ivy.

I do my heavy structural pruning in January when the tree is fully dormant. This triggers a vigorous response in spring. Since the main crop grows on new wood, the more new growth I stimulate, the more figs I harvest in August. It is a direct correlation. If I skip pruning, my yield drops by about 40% the following season.

- Sanitation Pruning: First, I remove any dead, diseased, or crossing branches that rub against each other.

- Height Reduction: I cut the main vertical branches back by one-third to encourage lateral branching.

- Thinning: I remove inward-growing branches to ensure sunlight hits the center of the tree, keeping the interior dry and fungal-free.

- Sucker Removal: I cut off all suckers sprouting from the base of the trunk (the rootstock) immediately, as they sap energy from the fruit.

The Harvest: Timing is Everything

Understanding when to pick a fig is an art form that took me three seasons to master. Unlike a banana or an avocado, a fig stops ripening the moment you pull it from the stem. If you pick it early, you have a crunchy, tasteless ball of latex. I look for the “droop.” The neck of the fruit should soften, causing the fig to hang vertically rather than sticking out sideways.

The ultimate ripeness test is the “tear in the eye.” A perfectly ripe Brown Turkey Fig will often have a tiny drop of nectar oozing from the ostiole (the eye) at the bottom of the fruit.

I remember one specific harvest in late August where I got greedy. I saw the figs were purple but still standing up straight. I harvested 40 pounds of them to take to the market. I couldn’t sell a single one. They tasted like cardboard. I had to compost the entire batch. That was a $300 lesson in patience. Now, I touch every single fig before I pick it. It should feel like a partially inflated water balloon—soft and yielding.

Nutritional Profile and Culinary Use

These fruits are not just sugar bombs; they are nutrient-dense. A medium fig contains about 8 grams of carbohydrates, but also significant potassium and dietary fiber. Our team at Exotic Fruits and Vegetables loves recommending Brown Turkey figs for preservation because their skin is slightly tougher than other varieties, meaning they hold their shape better when cooked.

| Feature | Brown Turkey | Black Mission | Kadota |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin Color | Copper/Purple | Deep Blue/Black | Yellow/Green |

| Flavor Profile | Mild, Melon-like | Rich, Jammy | Honey, Intense |

| Harvest Window | May (Breba) & Aug-Oct | June & Aug-Nov | Aug-Oct (One crop) |

| Split Resistance | Moderate | Low | High |

While fresh eating is delightful, the real versatility shines in the kitchen. I prefer to slice them in half, brush them with olive oil, and grill them face down for 2 minutes until caramelized. The heat intensifies the sugars and adds a smoky complexity that pairs perfectly with goat cheese.

Troubleshooting: Fighting the Enemies

It’s not all sunshine and smooth sailing. We battle pests here constantly. The primary enemy in San Diego is the Fig Beetle (Cotinis mutabilis). These clumsy, iridescent green bombers can devour a ripe fig in an hour. Rhetorical question for you: How do you stop a beetle that can fly?

I don’t use pesticides because I eat this fruit straight off the tree. Instead, I use exclusion. I bag my best trophy clusters in organza mesh bags (the kind used for wedding favors) once they start to change color. It’s tedious labor, bagging hundreds of fruits, but it guarantees a harvest.

If you see knots or swelling on your roots during transplanting, you likely have Root-knot Nematodes. This microscopic pest is a death sentence for figs in sandy soil and requires aggressive soil solarization to fix.

Another issue is Fig Rust, a fungal infection that turns leaves bronze and causes them to drop early. This usually happens when we get unusual humidity or late rains. Through our work with Exotic Fruits and Vegetables farm, we have developed a protocol of spraying a copper fungicide in late winter just before bud break to kill overwintering spores. This preventative measure is far more effective than trying to treat the leaves once the rust appears.

Why the Brown Turkey Wins

So, what’s the catch? Why isn’t every tree a Black Mission or a Panache? The Brown Turkey wins on volume and reliability. It produces heavily even after a hard pruning or a drought year. In my orchard, a single mature tree yields roughly 40 to 50 pounds of fruit per year. That is an insane return on investment for a plant that I only fertilize twice a year with a standard 10-10-10 granular mix.

Here are the key reasons I keep planting them:

- Hardiness: They survive temperature drops to 10°F, which is well below anything San Diego throws at us.

- Self-Fertile: You don’t need the specialized fig wasp to pollinate them; they set fruit all by themselves.

- Rapid Growth: I have seen cuttings grow 6 feet in a single season.

- Pest Tolerance: While beetles love the fruit, the tree itself is virtually immune to most boring insects due to its sap.

If you are limited on space, Brown Turkey is the superior choice because it responds best to container culture, thriving in a 15-gallon pot on a balcony.

Final Thoughts from the Field

Growing your own food changes your relationship with taste. When you bite into a store-bought fig, it has often been refrigerated, which kills the flavor profile completely. When you eat a warm fig standing next to the tree that grew it, you taste the soil, the sun, and the months of patience.

The satisfaction of peeling open a warm, soft fig and seeing that rose-quartz colored interior is one of the highest rewards in farming.

The Brown Turkey fig is not just a plant; it is a legacy you leave for the next generation, as these trees can easily live and produce for over 50 years.

If you have a patch of dirt and access to sunlight, put one in the ground this weekend. Don’t overthink it. Dig the hole, plant the stick, and watch it take over. Nature wants to grow; sometimes we just need to get out of the way and let it happen.