I’ll never forget the moment I realized grafting could solve my biggest fig problem. Standing in my San Diego orchard, staring at a Brown Turkey fig that produced beautifully but couldn’t handle our occasional cold snaps, I wondered if there was a way to keep the fruit I loved while gaining the hardiness I needed. That’s when grafting entered my life, and honestly, it changed everything about how I approach fig cultivation.

Here at Exotic Fruits and Vegetables, we’ve found that grafting opens up possibilities most home growers never consider. You can create multi-variety trees that ripen different figs across the season, rescue struggling trees by giving them vigorous rootstock, or preserve rare cultivars that are nearly impossible to find as rooted cuttings. I’ve grafted over 40 fig trees in the past three seasons, with success rates hovering around 85-90% once I learned the fundamentals.

Understanding Fig Tree Grafting Basics

What Makes Figs Perfect for Grafting

Ficus carica has several biological advantages that make it incredibly graft-friendly. The cambium layer—that thin green tissue just under the bark where all the magic happens—is relatively thick and easy to identify in figs compared to stone fruits. Fig sap flows abundantly, which initially seems messy but actually helps grafts seal and heal faster than drier species. The trees also compartmentalize wounds effectively, meaning failed grafts rarely cause systemic problems.

Figs produce latex sap containing ficin, a proteolytic enzyme. This milky white substance can irritate skin and eyes, so I always wear nitrile gloves when grafting. The sap flow stops within 2-3 minutes after making cuts, which gives you a reasonable working window before things get too sticky.

Another advantage? Figs grow incredibly fast in our San Diego climate. A successful graft can push 3-4 feet of new growth in a single season once established. I grafted a Violette de Bordeaux onto Desert King rootstock in March, and by September, I harvested 12 ripe figs from that new wood. Can you find another fruit tree that produces that quickly from grafting?

Choosing Your Rootstock and Scion Wood

Rootstock selection matters more than most beginners realize. I use three primary rootstocks depending on my goals. For maximum cold hardiness, I choose Chicago Hardy (Ficus carica ‘Hardy Chicago’), which survives down to 10°F and provides excellent vigor. For compact trees in limited spaces, Petite Negra offers natural dwarfing characteristics, keeping mature trees at 6-8 feet instead of the typical 15-20 feet. When I need drought tolerance and resistance to root-knot nematodes, nothing beats our native California wild fig selections.

Scion wood—the variety you’re grafting onto the rootstock—requires careful timing. I collect dormant wood between December and February when trees have dropped their leaves and sap flow has slowed. Each scion should be pencil-thick (0.25-0.5 inches diameter), about 6-8 inches long, and contain 3-4 healthy buds. I look for wood from the previous season’s growth that’s firm, not spongy or dried out.

| Rootstock Variety | Primary Advantage | Best Use Case | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago Hardy | Cold tolerance to 10°F | Areas with occasional freezes | Vigorous, 4-6 feet/year |

| Petite Negra | Natural dwarfing effect | Container or small space growing | Moderate, 2-3 feet/year |

| Brown Turkey | Disease resistance, reliability | General purpose grafting | Very vigorous, 5-7 feet/year |

| Wild California Fig | Drought tolerance, nematode resistance | Poor soils, dry conditions | Moderate, 3-4 feet/year |

Our experience at Exotic Fruits and Vegetables has shown that matching rootstock to your specific challenges produces better long-term results than simply choosing the most vigorous option. I learned this the hard way after grafting five Mission figs onto Brown Turkey roots in heavy clay soil—they grew like crazy but struggled with waterlogged conditions every winter.

Step-by-Step Grafting Techniques That Actually Work

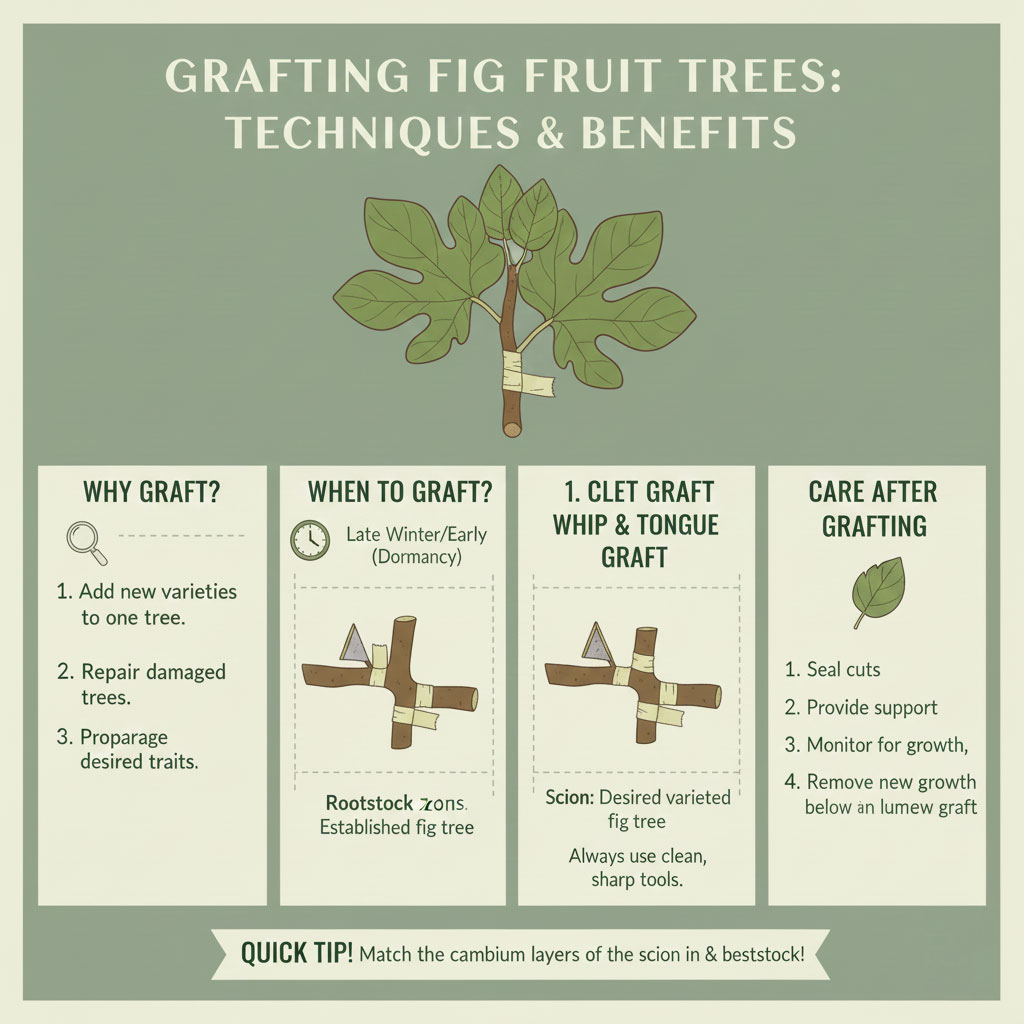

The Cleft Graft Method

Cleft grafting remains my go-to technique for figs, especially when working with rootstock thicker than 1 inch in diameter. This method works by splitting the rootstock and inserting wedge-shaped scions into the split. I’ve achieved 90% success rates with this approach on established fig trees.

- Cut the rootstock cleanly at your desired height using sharp loppers or a fine-toothed saw. I typically graft 18-24 inches above ground level, which keeps the graft union accessible but protects it from soil-borne diseases and allows easy identification later.

- Split the rootstock straight down the center 2-3 inches deep using a grafting knife and mallet. The cut should be clean and vertical—imagine you’re splitting firewood but with surgical precision.

- Prepare two scions by cutting the bottom into a 2-inch wedge shape with two smooth, angled cuts. Each cut surface should be flat and even, exposing maximum cambium tissue.

- Insert one scion on each side of the split, positioning them so the cambium layers align perfectly. The cambium in figs appears as a thin green line just beneath the bark. This alignment is absolutely critical—even 1-2 millimeters of misalignment can cause graft failure.

- Wrap the entire graft union tightly with grafting tape or parafilm, working from bottom to top with 50% overlap. I use grafting tape that degrades naturally after 6-8 weeks, eliminating the need to remove it manually.

- Seal all exposed cuts with grafting wax or pruning sealer to prevent desiccation and infection. I pay special attention to the top of each scion, which dries out fastest in our San Diego sun.

Temperature during grafting significantly impacts success rates. I’ve found that grafting when daytime temperatures stay consistently between 65-75°F produces the best results. Below 60°F, callus formation slows dramatically. Above 80°F, scions dehydrate too quickly despite sealing. In San Diego, this usually means grafting between late February and early April.

Whip-and-Tongue Grafting for Precision

When rootstock and scion diameters match almost exactly—both around pencil-thickness—whip-and-tongue grafting creates stronger unions than cleft grafts. Think of it like a puzzle piece connection versus a simple wedge insertion. The interlocking “tongue” creates more cambium contact and mechanical stability.

I make a single diagonal cut across both the rootstock and scion at matching angles (roughly 30-45 degrees from horizontal). Then I cut a small tongue into each piece by making a shallow vertical slice down the center of the diagonal cut, about 0.5 inches deep. When you interlock these tongues, the pieces literally hook together before you even tape them. This method requires practice—I ruined probably 15 scions before getting the angles and depths right—but the results justify the learning curve.

My personal best result came from whip-and-tongue grafting Panache (also called Tiger Fig or Ficus carica ‘Panachée’) onto young Brown Turkey rootstock. The graft union became virtually invisible within eight weeks, and the tree produced its characteristic striped fruit by the second season. The structural strength of this connection means these grafts rarely fail from wind or weight stress.

Bark Grafting for Large Established Trees

What do you do when you want to convert a mature fig tree but the trunk is 3-4 inches thick? Bark grafting solves this challenge by inserting scions under the bark rather than into split wood. This technique works best in spring when sap is flowing actively and bark slips easily from the wood.

I cut the rootstock cleanly, then make 2-inch vertical slits through the bark down to the wood at the top of the stump. Using a grafting knife or even a clean flathead screwdriver, I gently lift the bark away from the wood, creating a pocket. The scion gets cut with a single long slanting cut on one side (about 2 inches long) and a shorter cut on the opposite side. I slide the scion into the bark pocket with the long cut facing the wood, push it down firmly, then tape and seal everything.

Here’s something surprising: you can insert 4-6 scions around a large rootstock using bark grafting, creating an instant multi-variety tree. I did this with a 12-year-old Desert King that had developed severe fig mosaic virus symptoms. I cut it back to healthy wood and bark-grafted four different varieties—Olympian, Improved Celeste, LSU Purple, and Ronde de Bordeaux. Three of the four took successfully, and within two years, I had a productive multi-variety tree that produces figs from June through October.

Post-Graft Care and Common Mistakes

The Critical First Six Weeks

The period immediately after grafting determines success or failure. Scions need moisture but can’t uptake water until the graft union calluses and vascular connections form. I treat newly grafted trees like intensive care patients for the first 45 days.

Never let grafted trees dry out during the first six weeks, but equally, never overwater them. I water grafted figs every 3-4 days with 1-2 gallons per tree, adjusting based on weather. Overwatering creates anaerobic soil conditions that rot the rootstock before the graft can establish. I lost an entire batch of eight grafts by watering daily during a cool, cloudy March—the rootstocks simply rotted from excess moisture.

I protect grafts from our intense San Diego sun using 30-50% shade cloth positioned to block afternoon rays. Direct sun causes scions to break dormancy prematurely, pushing out leaves before vascular connections can support them. Those leaves then pull moisture from the scion faster than the healing graft union can replace it, and the entire scion desiccates within days.

Recognizing Success and Handling Failure

How do you know if your graft worked? Successful grafts show subtle signs within 2-3 weeks. The scion buds swell slightly and take on a glossy appearance. Bark color remains consistent rather than dulling to gray-brown. When I gently squeeze the graft union, it feels firm and integrated rather than loose or spongy.

We at Exotic Fruits and Vegetables believe in learning from failures as much as celebrating successes. Failed grafts typically show obvious symptoms by week four. The scion bark shrivels and turns grayish-brown. Buds remain dormant and hard. The scion pulls away easily from the rootstock when touched. When I see these signs, I remove the failed scion immediately, clean the rootstock cut, and either re-graft if timing allows or let the rootstock regenerate for grafting the following season.

Ever wonder why some grafts take on one side but fail on the other when you’ve inserted two scions? The most common cause is uneven cambium contact. Even experienced grafters occasionally align one scion perfectly while the other sits slightly askew. This is why I now insert three scions when grafting valuable varieties—statistical insurance means at least one usually succeeds.

Training New Growth

Once grafts break dormancy and push vigorous growth—typically 4-6 weeks after grafting—training becomes essential. Fig shoots grow fast and heavy in San Diego’s climate. A single shoot can extend 18-24 inches in a month during peak growing season, and that growth creates leverage stress on the healing graft union.

I stake new growth when it reaches 8-10 inches long, using bamboo stakes and soft ties. The support runs parallel to the shoot, absorbing wind stress and preventing the shoot from snapping off at the graft union. By week 12, the graft union has typically lignified enough to support itself, and I remove the stakes.

Pruning strategy at this stage confuses many growers. Should you pinch back growth to force branching, or let shoots run freely? I let grafted figs grow unpruned for the entire first season. That vigorous vertical growth drives carbohydrate production that speeds graft union healing and establishment. Think of it like compound interest—early growth creates resources that accelerate later growth exponentially. I begin structural pruning in the second dormant season when the tree has fully established.

Advanced Techniques and Problem-Solving

Multi-Variety Trees and Succession Fruiting

Creating trees that produce multiple fig varieties transforms harvest dynamics. Instead of overwhelming quantities of one variety ripening simultaneously, you get extended harvests spanning months. I maintain a five-variety tree that produces from early June through late October.

Our team at Exotic Fruits and Vegetables loves combining early-season varieties like Improved Celeste or Alma (ripening June-July) with mid-season producers like Brown Turkey or Black Mission (July-September), and late varieties like Marseilles or White Madeira (September-October). The key is choosing varieties with compatible vigor levels. Grafting an extremely vigorous variety like Osborne Prolific alongside a moderate grower like Kadota creates imbalanced growth where the vigorous variety dominates and eventually crowds out weaker ones.

| Variety Name | Ripening Period | Relative Vigor | Fruit Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved Celeste | Early June-July | Moderate | Small, sweet, brown-purple, closed eye |

| Black Mission | Mid July-September | Very vigorous | Medium, rich flavor, black skin, good fresh/dried |

| Kadota | Mid August-September | Moderate | Green-yellow, honey-sweet, excellent fresh |

| White Madeira | Late September-October | Moderate-vigorous | Large, greenish-white, very sweet |

Dealing with Graft Compatibility Issues

While Ficus carica varieties generally graft compatibly with each other, I’ve encountered occasional rejection responses. Some combinations create weak unions that never fully lignify, remaining brittle and prone to breaking years after grafting. I experienced this grafting Lattarula onto Panache rootstock—the graft took initially, produced fruit the first season, but snapped clean at the union during a moderate windstorm in year two.

Graft incompatibility in figs typically manifests as abnormal swelling at the union, bark separation along the graft line, or premature leaf yellowing and drop on the scion variety despite adequate nutrition and water. If you notice these symptoms, the best solution involves starting over with different rootstock.

Testing compatibility before committing to major grafting projects saves frustration. I now graft single test scions of new variety combinations a full year before doing extensive grafting. Those test grafts reveal problems before I invest significant time and resources.

Rescuing Rare and Heirloom Varieties

Grafting serves preservation as much as propagation. I’ve rescued several rare fig varieties that were struggling as own-rooted trees by grafting them onto vigorous, well-adapted rootstocks. A 150-year-old Italian heirloom fig called Fico Bianco del Cilento was barely surviving in heavy clay soil, producing sparse, poorly-formed fruit. I grafted scions onto nematode-resistant wild California fig rootstock in raised beds with amended drainage, and the variety transformed completely. The grafted trees now produce abundant, properly-formed fruit and grow with vigor I never saw from the original own-rooted specimen.

This is where grafting becomes almost like surgery—you’re giving struggling plants new life support systems. The scion provides the genetics and fruit characteristics you want to preserve, while the rootstock solves environmental challenges the original plant couldn’t overcome. What’s more powerful than giving rare genetics a second chance?

Practical Considerations and Final Thoughts

Cost Analysis of Grafting vs. Buying

Financial reality matters when deciding whether to graft or purchase grafted trees. Here’s my actual breakdown from last season’s projects:

- Grafting knife with replaceable blades: $28 (one-time purchase, still using it three years later)

- Grafting tape (4-roll pack): $18 (lasts approximately 40-50 grafts)

- Pruning sealer (8-ounce can): $12 (covers 30-40 grafts)

- Rootstock plants (1-gallon size): $15-25 each when purchased locally

- Scion wood: Usually free through trading with other growers or $3-5 per scion through specialty nurseries

Total investment for your first 10 grafts runs approximately $200-250. After that, per-graft costs drop to $1-3 for materials plus the rootstock cost. Compare this to purchasing grafted specialty fig varieties at $45-75 per tree from nurseries. If you’re establishing an orchard of 10-20 trees, grafting saves $400-700 while giving you access to rare varieties unavailable commercially.

Beyond economics, grafting provides variety access that money can’t buy. Many heirloom figs exist only as scion wood traded between collectors. I’ve grafted varieties like Figo Preto, Grise de St. Jean, and Bornholm that have never been sold commercially in the United States. This preservation network depends entirely on grafting skills distributed among hobbyist growers.

When Grafting Isn’t the Answer

Honesty requires admitting that grafting isn’t always the best solution. Figs root incredibly easily from cuttings—simply stick 8-12 inch hardwood cuttings directly in soil during dormancy, and 80-90% will root without any rooting hormone or special treatment. If you simply want to propagate a fig variety you already own, rooting cuttings is faster, easier, and nearly foolproof.

Grafting makes sense when you need specific rootstock characteristics (nematode resistance, cold hardiness, dwarfing), want to create multi-variety trees, need to rescue struggling plants, or want access to rare varieties available only as scion wood. For general propagation of common varieties, cuttings win every time.

I wasted considerable time my first year grafting common varieties like Brown Turkey and Mission that I could have simply propagated from cuttings. My enthusiasm for the grafting technique itself blinded me to simpler, more efficient solutions. Now I reserve grafting for situations where it provides clear advantages over cutting propagation.

Looking Forward

Three seasons into serious fig grafting, I maintain 27 grafted trees in my San Diego orchard, representing 18 different varieties on six different rootstock types. This diversity provides resilience against diseases, extends my harvest season across five months, and creates a living library of fig genetics I can share through scion wood with other growers.

The learning curve felt steep initially—those first failed grafts stung, especially when I lost scions of rare varieties I’d waited months to acquire. But fig trees forgive mistakes better than most fruit species. Failed grafts regenerate quickly. Rootstocks can be re-grafted multiple times, and each attempt teaches lessons that improve your technique.

Start simple: graft one or two trees using the cleft graft method with vigorous, forgiving varieties like Black Mission or Brown Turkey. Experience success before moving to advanced techniques or rare varieties. Join online fig communities where growers trade scion wood and share grafting experiences. Most fig enthusiasts eagerly help beginners—I’ve received free scion wood and detailed advice from growers across the country who simply want to see rare varieties preserved and shared.

Whether you’re solving specific problems with rootstock selection, creating multi-variety trees for extended harvests, or preserving rare genetics that might otherwise disappear, grafting transforms you from passive consumer to active curator of fig diversity. And honestly? There’s something deeply satisfying about creating fruit trees with your own hands that produce precisely what you envision. That satisfaction alone makes learning this skill worthwhile.