There is nothing quite like standing in your own backyard on a warm San Diego morning, reaching up, and plucking a fruit that feels like a soft, heavy teardrop of honey. I am talking about the fig. If you have only ever eaten the dry, crunchy centers of a Newton cookie, you have been missing out on one of nature’s most luxurious treats. Growing a fig tree here in Southern California is almost a rite of passage for us growers; the Mediterranean climate mimics their homeland perfectly, yet I still see people struggle with them every season.

Here at Exotic Fruits and Vegetables, we’ve found that the biggest barrier to success isn’t the difficulty of the plant, but rather the misinformation surrounding its water and nutrient needs. I want to walk you through exactly how I manage my orchard, mistakes and all, so you can skip the trial and error and get straight to the harvest.

Choosing the Right Variety and Location

Before you even pick up a shovel, you have to understand that not all figs behave the same way. In San Diego, we are blessed with a lack of fig wasps (which are required for pollinating some Old World varieties like Smyrna), so we rely on “common” type figs that are self-pollinating. If you plant a Smyrna here, you will grow a beautiful shade tree that never produces a single edible fruit.

Did you know that the fig is technically an inverted flower? The “fruit” is actually a syconium, a fleshy stem containing hundreds of tiny flowers inside.

I currently grow about twelve different cultivars, but I always recommend starting with the proven winners for our Zone 10 climate. The Black Mission is the heavy lifter of the industry, reliable and incredibly sweet. However, my personal obsession lately is the Panachée, or “Tiger Stripe” fig. It has yellow and green stripes and tastes distinctly like strawberry jam, but it requires significantly more heat units—roughly 100 hours of temperatures above 90°F—to ripen fully compared to the Brown Turkey.

| Variety | Skin Color | Flavor Profile | San Diego Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black Mission | Deep Purple/Black | Rich, earthy sweetness | Excellent; produces two strong crops annually |

| Brown Turkey | Copper/Brown | Mild, sugary | Reliable; great for coastal areas with less heat |

| Panachée (Tiger) | Yellow/Green Stripe | Berry-like, acidic tang | High; needs inland heat (El Cajon/Escondido areas) |

| Desert King | Green | Melting, light sweetness | Best for the early “Breba” crop in June |

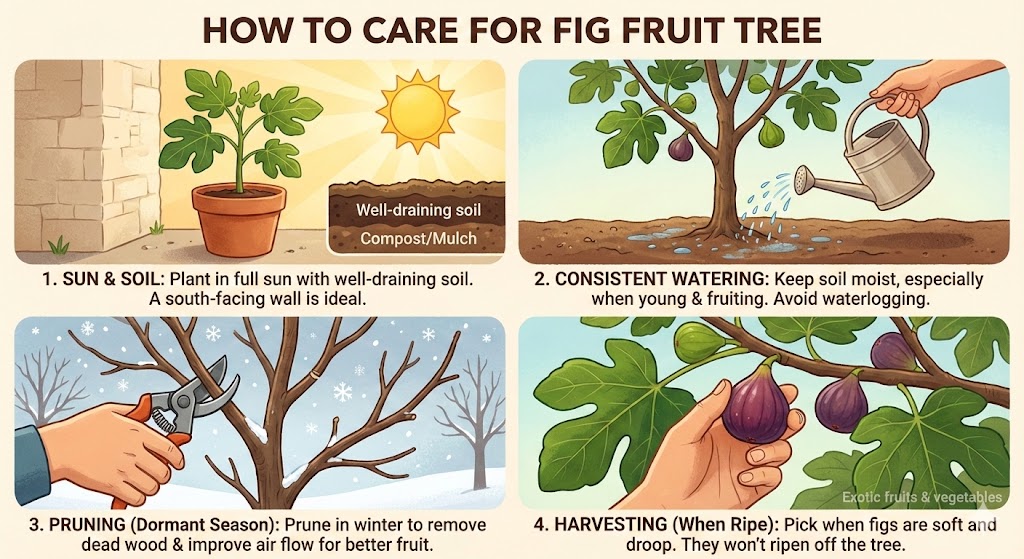

Location is non-negotiable. You need full sun. I don’t mean “bright shade” or “morning sun”; I mean at least 8 to 10 hours of direct, unadulterated sunlight. I once tried to tuck a Celeste fig into a corner that got shaded by my neighbor’s eucalyptus after 2:00 PM. The tree grew leggy, spindly, and produced fruit that tasted like watered-down cucumber.

Never plant a fig tree within 20 feet of your foundation, sewer lines, or septic tank. Their roots are aggressive, thirsty explorers that will crack pipes to find water.

Soil Preparation and Planting

Figs are not terribly picky about soil pH, tolerating a range from 6.0 to 7.8, but they absolutely demand drainage. Our heavy clay soils in parts of San Diego can be a death sentence. Think of the soil as the tree’s lung; if it is full of water, the tree suffocates. When I plant a new tree, I dig a hole twice as wide as the pot but no deeper. I mix the native soil 50/50 with cactus mix or a sandy loam amendment containing at least 30% perlite.

My breakthrough came when I stopped trying to spoil the tree with rich potting soil in the ground. When the planting hole is too rich compared to the surrounding native dirt, the roots stay in the hole, creating a “pot” effect in the ground. You want those roots to venture out.

The Planting Process

When you put the tree in the ground, plant it slightly deeper than it was in the pot—about 2 to 4 inches deeper. This is different from almost every other fruit tree. Why? Because Ficus carica can grow roots from its trunk, and burying it deeper anchors it against our Santa Ana winds and protects the root crown from drying out.

Ever wonder why some young trees stall and refuse to grow for the first year? It’s usually “transplant shock” caused by insufficient water contact with the roots immediately after planting.

Watering: The Goldilocks Zone

This is where I see most people fail. They treat figs like desert cactuses because they look rugged. While an established fig can survive a drought, it won’t produce juicy fruit without water. Fruit consists of water and sugar; without the water, the factory shuts down.

For a young tree (years 1-2), I water deeply—about 5 to 10 gallons—twice a week during the summer. For mature trees, I back off the frequency but increase the volume. I run a drip line that delivers roughly 30 gallons of water over a 4-hour period, once every 10 days in the summer heat. If we hit a heatwave with temps over 95°F, I bump that to once a week.

Inconsistent watering is the number one cause of fruit splitting. If the tree goes dry and then gets a flood of water, the fruit swells faster than the skin can stretch, and it pops open like a zipper.

Our experience at Exotic Fruits and Vegetables has shown that mulching is the secret weapon for moisture management. I apply a 4-inch layer of wood chips or straw in a donut shape around the base of every tree, keeping it 6 inches away from the trunk to prevent collar rot. This reduces evaporation by nearly 50% and keeps the shallow feeder roots cool.

Feeding and Pruning for Production

Figs are vigorous growers. If you feed them too much nitrogen, they will reward you with 10 feet of gorgeous green growth and zero figs. It is a classic rookie mistake. I made this error five years ago with a Violette de Bordeaux; I gave it high-nitrogen lawn fertilizer, and it turned into a bush monster that didn’t fruit until I starved it the following year.

I fertilize only three times a year:

- Late winter (February) when buds swell.

- Late spring (May) after the first crop sets.

- Mid-summer (July) to support the main crop.

I use a balanced organic fertilizer with an N-P-K ratio of 5-5-5 or even lower on the nitrogen side. You don’t need fancy chemicals; a top dressing of composted chicken manure works wonders because it provides calcium, which prevents the fruit from rotting on the end.

The Art of Pruning

Think of pruning a fig tree like giving a poodle a haircut—you can’t really hurt it, and it will grow back faster than you expect. For optimal fruit production, I use the “Open Center” method. This involves clearing out the middle of the tree to let light hit every branch. Sunlight striking the wood stimulates fruit bud formation.

- Remove the Ds: First, cut out anything Dead, Damaged, or Diseased.

- Clear the Base: Remove all “suckers” (shoots growing from the root base) unless you are intentionally replacing an old trunk.

- Open the Middle: Select 3 to 4 main scaffold branches growing outward and cut the central leader trunk just above them.

- Head Back: Cut the remaining branches back by one-third to encourage branching.

“A properly pruned fig tree should allow a bird to fly through it without touching its wings on a branch.”

Pests and Problems

In San Diego, we don’t battle the cold, but we do battle the Figeater Beetle (Cotinis mutabilis). These iridescent green beetles are clumsy fliers but voracious eaters. They swarm ripe fruit and turn it into a fermented mess. I don’t use pesticides because I eat the skin.

Instead, I use exclusion. I bag my best clusters in organza mesh jewelry bags. It takes time, yes, but it guarantees a perfect harvest. Birds are the other thief. If you see a half-eaten fig, it was likely a mockingbird. Reflective tape or an owl decoy that you move every few days can help, but sharing a few figs with nature is often the price of admission.

The most devastating issue isn’t a bug, but a nematode. Root-knot nematodes are microscopic worms in sandy soils that cause gnarled roots and stunted growth.

If your tree looks thirsty even when the soil is wet, check the roots. If you have nematodes, the best defense is heavy organic matter. The beneficial fungi in compost attack the nematodes.

Harvesting: The Sweet Reward

Knowing when to pick is the difference between a mediocre fruit and a culinary masterpiece. A fig does not ripen off the tree. If you pick it firm, it stays firm. You are looking for the “droop.” When the neck of the fruit softens and the fig hangs straight down, heavily, it is ready.

I often look for a tiny tear in the skin or a drop of nectar at the eye (the opening at the bottom). That is the sugar trying to escape. As fruit enthusiasts at Exotic Fruits and Vegetables, we encourage you to eat them warm, straight from the branch. The flavor complexity of a sun-warmed fig is miles beyond anything you can buy in a plastic clamshell at the grocery store.

- Fresh Eating: Slice in half with goat cheese and honey.

- Drying: Dehydrate at 135°F for 12 hours for candy-like treats.

- Jams: The natural pectin makes them easy to preserve.

- Grilling: Brush with balsamic glaze and grill for 2 minutes—unbelievable.

I once ruined an entire batch of jam by picking the figs one day too early. They lacked the natural sugar, and I had to overcompensate with cane sugar, which drowned out the delicate floral notes. Wait for the droop!

Growing figs connects us to history. It is one of the oldest cultivated crops known to humanity, and yet, it fits perfectly into our modern San Diego lifestyle. Whether you have a quarter-acre in La Mesa or a large pot on a balcony in Downtown, you can grow this fruit.

Pro Tip: If sap gets on your skin during harvest, wash it off immediately with soapy water. Fig latex is photo-toxic and can cause a rash when exposed to sunlight.

Don’t be intimidated by the pruning or the water schedules. The fig tree is forgiving. It wants to grow, and it wants to feed you. Put it in the sun, give it some room to breathe, and watch the magic happen.

I built a DIY greenhouse for my fig trees using polycarbonate panels and a shade cloth with 50% coverage. The total cost was $1,200, with a heating system that uses a propane heater and a thermostat. Ventilation is key – I installed an exhaust fan with a thermostat to maintain a temperature range of 65-75°F. Compared to commercial kits, my build saves around $800 and provides better climate control. I’m considering adding a misting system to maintain 80-90% RH.